Introduction

The concurrent delay has been one of the debatable areas in construction delay claims often parties challenge each other as regards their responsibility for delays involved.

In a typical construction delay context, the contractor would seek an extension of time and additional costs on the basis that a delay has occurred to the performance of the contract for which the contractor is not responsible, and thus such a delay should be compensated by the employer by awarding an extension of time equal to the period of delay, and additional payment to cover additional costs in the delay period.

On the other hand, the employer would defend its position by alleging that its delay (alleged by the contractor) was concurrent to the contractor’s delay and thus the contractor’s delay negated his responsibility for being culpable. By defending its position, the employer would assert that the performance of the contract would anyway be delayed due to the contractor’s concurrent delays. By building a case as such, the employer would attempt to impose delay damages to the contractor.

This is where the requirement of who is responsible for what has happened would arise. Indeed, it is increasingly becoming critical to establish the responsibility of each party with respect to the delays alleged.

Concurrent Delay Explained

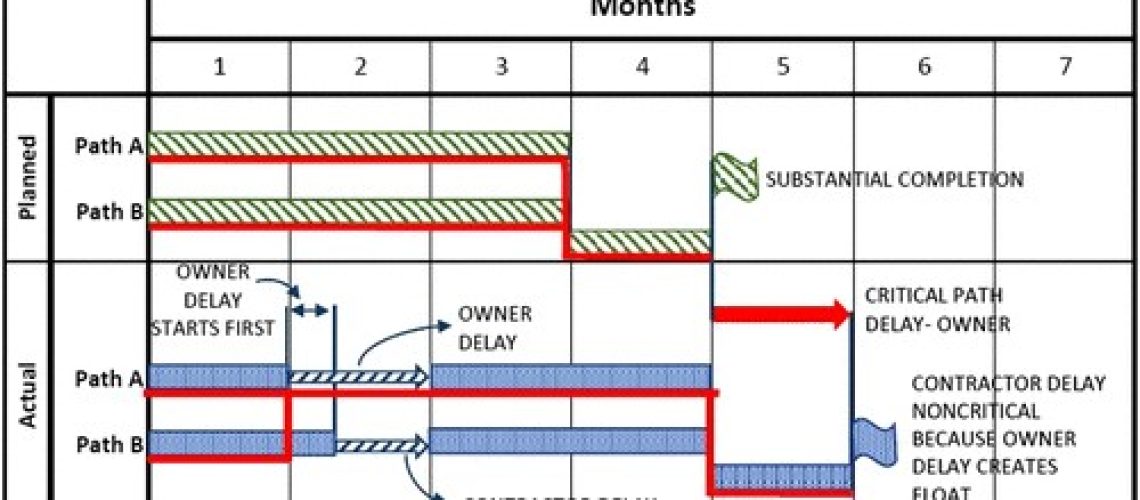

Concurrent delay refers to a circumstance or a situation where different causes of delay overlap with a particular period or schedule window[i]. Thus, a concurrent delay could occur to a window if a delay caused by the client[ii] is on the same activity path or a delay caused by the contractor[iii] to an activity that is on a parallel activity path. The delays that were caused both by the contractor and the client either affect the same activity or different activities on parallel activity paths which are equally critical[iv].

In a summary, the delay caused by the client and the delay caused by the contractor would each have delayed the completion date of the project, which is called to be concurrent[v].

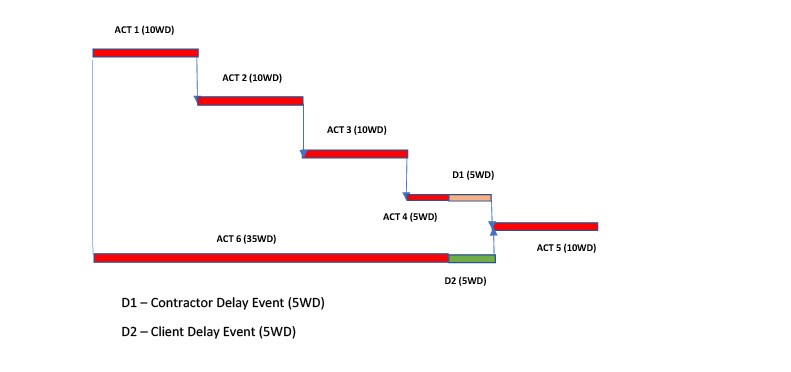

In the below example, the contractor caused a delay of 5 days on the Activity Path (Activity 1 to 4) and the client caused a delay of 5 days on the Activity Path (Activity 5 to 4) are independent delays and these two activity paths are equally critical, meaning the float value of these paths are the same, i.e., zero (0), and delays on these parallel paths have contributed to the completion of the project. This explains that the delay caused on the Activity Path (1 to 4) is the result of the contractor’s risk under the contract, whilst the delay caused on the Activity Path (5 to 4) is the result of the client’s risk under the contract.

His Honour Judge Seymour Q.C., in Royal Brompton Hospital NHS Trust v. Frederick A Hammond (No. 1), stated that:

However, it is, I think, necessary to be clear what one means by events operating concurrently. It does not mean, in my judgement, a situation in which, work already being delayed, let it be supposed, because [the Contractor] has had difficulty in obtaining sufficient labour, an event occurs which is a [Employer’s time risk event] and which, had [the Contractor] not been delayed, would have caused him to be delayed, but which in fact, by reason of the existing delay, made no difference. In such a situation although there is a [Employer’s time risk event], the completion of the works is [not] likely to be delayed thereby beyond the completion date’. The [Employer’s time risk event] simply has no effect upon the completion date. This situation obviously needs to be distinguished from a situation in which, as it were, the works are proceeding in a regular fashion and on programme, when two things happen, either of which, had it happened on its own, would have caused delay, and one is a [Employer’s time risk event], while the other is not. In such circumstances, there is a real concurrency for causes of the delay.[vi]

The Society of Construction Law, SCL Delay and Disruption Protocol 2nd edition, February 2017, states that:

“True concurrent delay is the occurrence of two or more delay events at the same time, one an Employer Risk Event, the other a Contractor Risk Event, and the effects of which are felt at the same time. For concurrent delay to exist, each of the Employer Risk Event and the Contractor Risk Event must be an effective cause of Delay to Completion (i.e. the delays must both affect the critical path). Where Contractor Delay to Completion occurs or has an effect concurrently with Employer Delay to Completion, the Contractor’s concurrent delay should not reduce any EOT due”[vii]

Other sources that have defined the concurrent delay include AACE International[viii] Recommended Practice:[ix]

- Two or more delays that take place or overlap during the same period, either of which occurring alone would have affected the ultimate completion date.

- Concurrent delays occur when there are two or more independent causes of delay during the same time period. The “same” time period from which concurrency is measured, however, is not always literally within the exact period of time.

The AACE Recommended Practice RP 29R-03 suggests a series of tests for the existence of concurrency delays[x]:

- Two or more unrelated, independent delays exist. One of these delays can be a delay arising from a force majeure event.

- None of the delays identified in Step 1 can be voluntary delays.

- Not all delayed activities identified in Step 1 are the responsibility of only one contracting party.

- The project completion date would have been delayed in the absence of any of the delays identified in Step 1.

- The delayed work must be substantial (i.e., not easily correctable).

Concurrent Delay and Contractual Issues

The contractual issues that arise from concurrency situations are quite complex and contentious due to the involvement of multi parties in construction developments as well as inconsistencies existing in defining and assessing the concurrent delay among courts, boards established by the contracts, arbitration and adjudication panels, and experts. The inconsistencies are predominantly to the fact of either the contract is silent on the matter, or the contractual provisions agreed upon are ambiguous[xi]. Thus, parties are prepared to deal with inconsistencies arising from the contract and the complex nature of concurrent delays. In the absence of clear provisions, the industry is supported by the guidelines issued by leading professional organizations such as AACE International and the Society of Construction Law (SCL) are significant.

The key contractual issues associated with concurrent delays are standards in measuring concurrent delays, risk allocation, prevention principles, time-only award, time including money, liquidated damages, etc.

Concurrent Delay and Standards

There have been various schools of thought as to the establishment and measurement of concurrent delays and associated loss and expense. The view of English law is to follow civil law standards (i.e., the balance of probabilities – those more than 50%[xii]) to examine the cause of a delay that affects the project completion as concurrent delay involves more than a cause of delay. The term causation refers to the link and/or the relationship between the default of a party and the resultant actual delay and associated damages arising from such delay. Hence, establishing causation for delay claims is essential to determine the extent of damages the claimant is entitled to from the defendant[xiii]. Considering this, in a delay situation if the contractor alleged that the client’s default/breach caused the delayed completion, then, merely proving that the client is responsible for that alleged default/breach is not sufficient, rather it is necessary to prove that the client’s default/breach has actually caused those damages suffered by the contractor.

In contract law, the “but-for” test is a means of establishing “causation in fact” for which the civil law standard cited above has been in practice. The ‘but-for’ test refers to, ‘Was the damage caused by the defendant’s breach of duty?’.[xiv] In Cork v Kirby MacLean Ltd[xv] Lord Denning held that ‘…If the damage would not have happened but for a particular fault, then the fault is the cause of the damage; if it would have happened just the same, fault or no fault, the fault is not the cause of the damage’.

The but-for test encounters numerous difficulties in concurrent delay situations[xvi]. Moran QC attempted to determine whether “dominant cause tests’ and “approximately equal causative potency tests’ were valid means of measuring the concurrent delay and concluded these were not. Consequently, Moran QC suggested that an “effective cause test” is an approved means in Walter Lilly v Mackay[xvii], i.e., the test needs to define an effective cause as being one that causes a critical delay to the completion.[xviii] An effective concurrent cause can be established by a ‘reverse but-for test’. For loss and expenses associated with concurrency means contractors are required to satisfy a ‘but-for’ test or burden of proof.[xix]

Risk Allocation Among Parties

It is quite common that majority of the construction contracts do not contain provisions to adequately address the concurrent delay situations of a project thereby issues arise as to the liability of the parties. Nonetheless, it is up to the Parties to decide to include adequate provisions in the Contract to effectively administrate concurrent delay situations. The courts have often upheld the provisions agreed under the Contract for ruling disputes that arose from concurrent delay situations. In North Midland Building Ltd v Cyden Homes Ltd [2017],[xx] the Technology and Construction Court (TCC) clarified that the parties to a contract are free to agree on provisions to allocate risks associated with concurrent delay[xxi]

In a case, the contractor pursued a dispute that a provision agreed to disallow the extension of time in a concurrency situation has invalidated the prevention principle. The said contract was an amended JCT Design and Build Contract (2005 edition), in which the parties agreed to a provision stating that any delay caused by a Relevant Event (Employer Risk Event) concurrent with another delay for which the contractor is responsible shall not be taken into account when assessing a claim for an extension of time. The Court held that the provision is found to be “crystal clear” and thus the contractor’s argument that the agreed provisions did invalidate the prevention principle has no basis. The Court of Appeal upheld the TCC’s decision by stating that the clause in the contract that did not allow the contractor to an extension of time in circumstances of concurrent delay, was valid and could not be said to be uncommercial. The provision agreed upon by the parties places the benefit of the concurrent delay on the client.

Prevention Principle

The “prevention principle’ is a legal doctrine that protects a contractor from liquidated damages for delays caused by the principal. The basic idea is that a party to a contract should not be permitted to profit from its own default.[xxii] In other words, the prevention principle prevents a party, in the absence of clear terms to the contrary, from taking advantage of its own wrong[xxiii].

It has long been accepted that the prevention principle applies to every contract[xxiv]. The prevention principle was first acknowledged by the courts in the English case of Peak Construction (Liverpool) Ltd v McKinney Foundations Ltd. In this case, the contractor was delayed by the client’s failure to give prompt instructions to proceed with certain works. No provision was existing in the contract to extend the time for completion. Thus, held that it was ‘beyond all reason’ to find the contractor liable to pay damages for the delay to the works.

In concurrent delay situations, a summary of the law on prevention and concurrent delay set out in the case of Jerram Falkus Construction Ltd v Fenice Investments Inc [2011] EWHC 1935 (TCC) is significant. According to it, the contractor shall demonstrate that the employer’s acts or omissions prevented the contractor from achieving an earlier completion date. If the completion of works would not have been achieved anyway, due to concurrent delays caused by the contractor’s own default, the prevention principle will not apply.

The contractor’s argument that the prevention principle should be applied to a concurrent context was ruled out by the TCC. This was in the case of North Midland Building Ltd v Cyden Homes Ltd [2017] EWHC 2414 (TCC), in which the contractor argued that a provision in the contract disallowed an extension of time in the concurrent delay context could not be valid due to the prevention principle. The contractor alleged that the agreed principle constitutes prevention by the employer from granting an extension of time and thus the time is at large and the liquidated damages provision void. TCC held that the prevention principle does not apply to cases of concurrent delay, for which previous authorities were cited by the court. In the case of Adyard Abu Dhabi v SD Marine Services [2011] EWHC 848 (Comm), the court maintained that the act of prevention of one party (employer) shall render it impossible or impractical for the other party to perform its obligation/work within the stipulated time. The logic is that such prevention cannot occur when the contractor is already in culpable delay.

Time without Money

The requirement of time extension to a contract is cited in an article published by Simmons +Simmons [xxv] which states that the “…Contractor is entitled to an extension of time where a delay is caused by the Employer because although the contractor must complete within a reasonable time, he must have a reasonable time within which to complete…”

This is in line with the general prevailing principle that, in a delay circumstance, if the completion of the project was delayed by a delay event (excusable and compensable) caused by the employer the completion of the contract will be extended together with an award for damages for the loss incurred by the contractor, subject to the contract terms or by the law.

Nonetheless, this widespread practice differs from a concurrency situation. The Core Principle of the Society of Construction Law and Disruption Protocol states that where the contractor incurs additional costs because of concurrent delays “… then the Contractor should only recover compensation if it is able to separate the additional costs caused by the Employer Delay from those caused by the Contractor Delay. If it would have incurred the additional cost in any event as a result of Contractor Delay, the Contractor will not be entitled to recover those additional costs.’

This principle indicates an exception to the award of damages to the contractor in circumstances where the completion of the project was delayed by more than one event concurrently for which parties are liable for their own delays. In the absence of either one party’s delay, the delay caused by another party will the delay completion. In such circumstances, the well-known practice that an extension of time is usually compensable will become non-compensable.

However, the contractor may be entitled to compensation for the loss incurred during the delay period that occurred beyond the concurrency. For instance, where a delay caused by the client was concurrent with an uncontrollable event (neutral risk) such as the client caused a delay of 20 days concurrent with 15 days of delay caused by rain. Then, 15 days of concurrent delays are not compensable but still, 5 days of delays are compensable. The damages to the 15 days concurrency are not payable to the contract because the contractor would have suffered the same loss as a result of a cause within his control or for which the contractor is contractually responsible.

Liquidated Damages and Prolongation Claim

Generally, the liquidated damages provision agreed in the Contract establishes damages (pre-agreed sum) to be paid by the Contractor to the Client in the event of delayed completion for which the Contractor is responsible. On contrary, if the completion of the project is delayed due to the Client’s risk events, the Contractor would be entitled to an extension of time and additional payment to cover the time-related costs incurred during the extended period. These illustrate two key damages claim associated with delayed completion: (i) liquidated damages and (ii) prolongation cost. Establishing the default of the parties in a concurrent delay situation is quite complex.

The Core Principle 10[xxvi] of the SCL Protocol defines the concurrent delay and effect on entitlement to the extension in such a way that a concurrent delay to exist, each of the Employer risk event and the Contractor risk event ‘must be an effective cause of Delay to Completion (i.e. the delays must both affect the critical path)’ The is referred to as a full extension of time[xxvii]. A critique around the principle is that employers lose the right to impose liquidated damages but are still expected to compensate for a contractor’s prolongation claim – called an ‘obverse problem’[xxviii] To avoid such a situation, based on the general principle, employers can claim unliquidated damages when contractors breach contracts. Similarly, Contractors will have the option to claim prolongation costs if they prove their entitlement or causation in the form of a ‘but-for’ test or burden of proof test.[xxix] The Core Principle 14[xxx] of the SCL Protocol supports this approach by stating the following:

“Where Employer Delay to Completion and Contractor Delay to Completion is concurrent and, as a result of that delay the Contractor incurs additional costs, then the Contractor should only recover compensation if it can separate the additional costs caused by the Employer Delay from those caused by the Contractor Delay. If it would have incurred the additional in any event as a result of Contractor Delay, the Contractor will not be entitled to recover those additional costs…”

The former part of this principle illustrates that unless losses are to be shared, the contractor cannot claim prolongation costs. The situation that could arise in such cases is out of two claims (liquidated damages and prolongation cost) one must succeed and the other must fail – called ‘obverse problem’

One of the other problematic areas in assessing parties’ entitlement to damages is in the context of ‘True Concurrency’. True concurrency refers to a situation in which the delay events caused both by the Client and the Contractor occurs at the same time including the effect of those delay events felt at the same time on the project’s critical path and completion. Hence, in a true concurrency context, the contractual responsibility for a delay to completion can be considered logically indeterminate because neither delay was necessary to cause a completion delay.[xxxi] As such, the prevailing argument is that the client will not be able to determine its entitlement to liquidated damages. Similarly, the Contractor will be unable to prove its entitlement to a prolongation claim. These concur with a substantial body of opinion that in concurrency situations, the Contractor is entitled to an extension of time without any compensation for additional costs incurred related to the extended period.

Conclusion

The current position of English Law, as to the concurrency delay situation is that: “It is now generally accepted that under the Standard Form of Building Contract and similar contracts a contractor is entitled to an extension of time where the delay is caused by matters falling within the clause notwithstanding the matter relied upon by the contractor is not the dominant cause of delay, provided only that it is an effective cause of delay ‘[xxxii] Having considered these contractual issues around the context of concurrent delay, one can understand that effectively addressing these issues requires unambiguous contractual provisions to be agreed by the parties for sharing risks. Nevertheless, following certain standards recommended by the industry sources such as the need for an ‘effective cause test’ for determining the extension of time and a ‘but-for’ test or ‘burden of proof approach[xxxiii] for assessing the related damages are very much relevant in a concurrency delay situation.

Bibliography

[i] “Window” refers to a particular period consisting of a start and end date. These dates represent the data date in which the schedule is updated for progress.

[ii] The term “Client” is referred to throughout the article to refer to the owner or employer, who is the contractual party of the project.

[iii][iii] The term “Contractor” is referred to throughout the article to refer to the constructor, who is the contractual party of the project.

[iv] The requirement of equally critical is important for different activities on parallel activity paths to measure the concurrent delay if any. In such a context the duration of each party delay and the float value of each activity needs to be examined to determine the exact concurrent delay.

[v] Richard J. Long, Analysis of Concurrent Delay on Construction Claims (2022), Long International

[vi] Royal Brompton Hospital NHS Trust v. Frederick A Hammond (No. 1). [2000] EWHC technology 39 at 31

[vii] SCL Delay and Disruption Protocol 2nd Edition, February 2017

[viii] AACE International, Recommended Practice (RP) IOS-90 entitled Cost Engineering Terminology

[ix] American Bar Association (ABA), Concurrent Delays: Definitional and Procedural Considerations (09 Dec 2019)

[x] AACE International, AACE International Recommended Practice No. 29R-03 Forensic Schedule Analysis (2011)

[xi] American Bar Association (ABA), Concurrent Delays: Definitional and Procedural Considerations, 09 Dec 2019.

[xii] Furst, para 9-090, cited in JB Kim, Concurrent delay: Unliquidated damages by employer and disruption claim by contractor, International Bar Association, December 2020.

[xiii] Legal Dictionary, Causation, 01 May 2016

[xiv] Studocu, Causation in Fact

[xv] [1952] 2 All ER 402

[xvi] Franco Mastrandrea, (2014) ‘Concurrent delay in construction – principles and challenges’ The International Construction Law Review, 31(1), 83–107, cited in JB Kim, Concurrent delay: Unliquidated damages by employer and disruption claim by contractor, International Bar Association, December 2020.

[xvii] [2012] EWHC 1773 (TCC).

[xviii] Vincent Moran QC, ‘Causation in Construction Law: The Demise of the “Dominant Cause” Test?’ (SCL paper 190, 2014) cited See n 16 above.

[xix] JB Kim, Concurrent delay: Unliquidated damages by employer and disruption claim by contractor, International Bar Association, December 2020

[xx] North Midland Building Ltd v Cyden Homes Ltd [2017] EWHC 2414 (TCC)

[xxi] Simmons Simmons, ‘Concurrent Delay in Construction Contracts’, 16 August 2018

[xxii] Morgan Mcintosh, ‘What is the Prevention Principle?”, Turtons, 20 October 2017

[xxiii] Alghussein Establishment v Eton College [1988] 1 WLR 587, cited in Herbert Smith Freehills, “The Prevention Principle – An Irreproachable Concept?, 27 July 2020, London.

[xxiv] Marrin; Dennys, 3-127; as per Vaughan Williams LJ in Barque Quilpe Ltd v Brown [1904] 2 KB 264 at 274

[xxv] Simmons + Simmons, “Concurrent Delay in Construction Contracts” 16 Aug 2018

[xxvi] Society of Construction Law Delay and Disruption Protocol, Core Principle 10 ‘Concurrent delay – effect on entitlement to EOT’ 2nd edn February 2017

[xxvii] See n 16 above.

[xxviii] John Marrin QC, ‘Concurrent Delay Revisited’ (Society of Construction Law paper 179, February 2013).

[xxix] Ibid, Furst, para 9-093.

[xxx] Society of Construction Law Delay and Disruption Protocol, Core Principle 14 ‘Concurrent delay – effect on entitlement to EOT’ 2nd edn February 2017

[xxxi] See n 19 above.

[xxxii] Furst, 1st supplement para 8-026

[xxxiii] Marrin; Moran; Furst chs 8, 9; SCL Protocol (2nd Edition) core principle 10 and 14, cited in See n 16 above.